New working paper: The role of energy price dispersion

The good news keep on coming: After my first academic paper got published in JEEM last month, my second PhD paper is now available as a ZEW Discussion Paper!

In it, Kathrine von Graevenitz, Elisa Rottner and I investigate how an increasing dispersion in firms’ energy prices can have adverse effects on energy intensity – and hence on emissions. That is worrying news because many governments around the world are pursuing climate policies like carbon pricing that drive up effective energy prices, while at the same time trying to shield their energy-intensive industries through policy exemptions and energy price subsidies. In the end, energy prices rise, but some firms – often the most energy-intensive ones – are affected much less by these price increases.

We show in a theoretical model that the resulting gap in energy prices can, in principle, undo the entire energy-saving effects of the overall energy price increase. This is due to a ‘reshuffling’ among the producers of energy-intensive products: Due to the overall price increase, firms with a relatively high energy price lose shares of the markets for energy-intensive products (like steel or petrochemicals). That reduces competitive pressure on those firms who maintain a relatively low energy price, leading them to increase their own market shares. But since firms with a low energy price produce the same products in a more energy-intensive way, this makes aggregate production of these goods more energy-intensive than before!

Data from Germany suggest that this might indeed have been happening: As the figure below shows, the energy intensity of German manufacturing increased from 2003 to 2017 despite an overall shift towards less energy-intensive products. That means: On aggregate, German manufacturing firms have been producing in an ever more energy-intensive way!

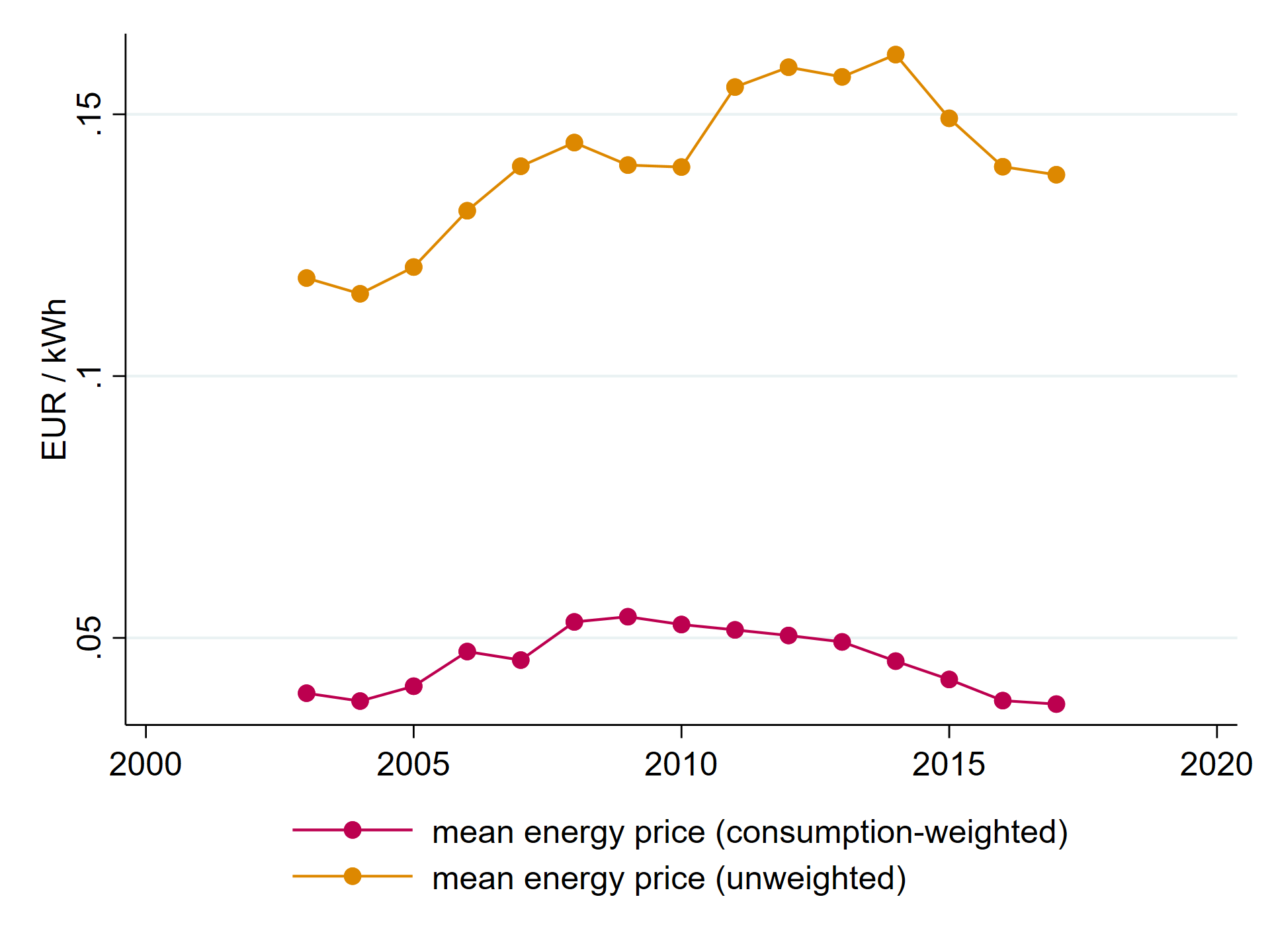

Over the same period, average energy prices have increased but not for the most energy-intensive firms.

Finally, regression analyses reveal that firms with a high energy price have disproportionally dropped out of the markets for energy-intensive products while firms with a low energy price have disproportionally entered these markets – just as our theoretically founded ‘reshuffling’ mechanism predicts.